Excellent tips for intelligent team working can be found from team studies across disciplines and domains. Here are some useful insights drawn from studies of high-performing teams working under pressure or with high demands or expectations placed upon them.

Project Aristotle

This is a well-known study by Google, which interviewed 180 internal teams and built models which used individual and team features to try to predict performance and positive experience. The top level conclusion was that process and other team-level characteristics were more important than those of the constituent individuals.

The following features proved the most significant indicators of team success:

- Dependability of teammates

- Personal meaning from the work

- Structure

- Impact of the work

- Psychological safety

Psychological safety was defined as the “shared belief held by team members that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking” and “A sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up”.

Recommendations for instilling a psychologically safe environment included: framing work as learning problems over and above execution problems; modelling curiosity and asking more questions; and admitting one’s own fallibility and epistemic humility (“I don’t know”, “I made a mistake”, “Can you teach me?”)

Sakaguchi, M. (2019) Our quest to build the most effective teams at Google https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vGn12DD2vZwSX2TEVVhNpap89mLedGga/view

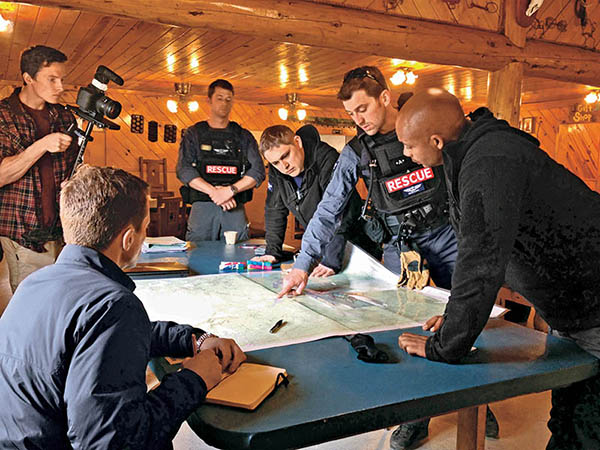

Rescue Global

This study analysed cooperative work in an NGO working in disaster relief. Teams here have to deal with a huge amount of uncertainty as to what the situation is on the ground, who needs help, what dangers exist, and what courses of action are optimal. The research highlighted the need for the team to have a shared artefact reflecting the ever-changing site situation, which they called the CRIP, or “Commonly Recognised Information Picture”.

The analysis noted four types of uncertainty that the teams deal with: environment, resources, equipment and information (Table). For me, the three most transferable insights here are the need for the common information picture; tool redundancy (back-up plans for when one approach or technique doesn’t work); and the need for unambiguous articulation work to combat information uncertainty, including work assignment and the importance of team members challenging each other on the justification for particular decisions.

| Principle | Uncertainty | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Deployable anywhere | Environment | What do we take with us? How do we operate it? |

| 2. Flexible support for situation analysis | Availability of resources | What local resources are available? |

| 3. Redundancy and graceful degradation (primary/secondary) | Equipment | What tools work, what if they fail? |

| 4. Support articulation work and accountability | Information | What is the situation? |

Fischer et al. (2015) Building a Bird’s Eye View: Collaborative Work in Disaster Response. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI ’15 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2702123.2702313

UK Premiership Rugby

This really nice paper followed a rugby team over the course of a season and analysed the behaviours and attitudes of players that contributed to both high performance and team resilience. What I liked most is how they translated between their own, academic interpretation of their content and the language and mantras or “folk terms” used by the players.

There are a number of great lessons from this work, particularly about the ability to bounce back from adversity through having a familiar structure to fall back on, and for the team to remind themselves, at a level where the pressures and expectations levels are constantly high, why they love what they do.

| Descriptor | Folk terms |

|---|---|

| Inspiring, motivating, and challenging team members to achieve performance excellence | “confident, not arrogant”, “step it up” |

| Develop a team-regulatory system based on ownership and responsibility | “captains on the field”, “character is defined when no one is watching” |

| Cultivate a team identity and a togetherness based on a selfless culture | “your body on the line”, “No egos here” |

| Expose the team to challenging training and unexpected/ difficult situations | “Keeping our structure”, “accuracy under pressure” |

| Promoting enjoyment and keeping a positive outlook during stressors | “play with smiles on our faces”,“keep the fun factor” |

Morgan, P. et al. (2019) Developing team resilience: A season-long study of psychosocial enablers and strategies in a high-level sports team. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 45, p. 101543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101543

In the Restaurant Kitchen

Kitchen teams of chefs, or brigades, have a clear hierarchical structure, but this observational study demonstrated how leadership becomes collaborative at ‘coup de feu’ moments of maximum stress when the kitchen is under fire, and when members must shift tasks and dynamically adjust to immediate challenges:

Another cook throws his pan into the sink rather than depositing it. David [head chef] makes no comment but he positions himself at the sink and takes ten minutes to clear the overflow of dirty dishes, to avoid the looming shortage that would inevitably disrupt the service. The sous-chef shuttles between the cold rooms and the cooking stations as he supplies the cooks. Several tables require service at the same time. Without consulting David, two cooks have been working together for ten minutes in the cooking section

Crucial service timings, as well as quality controls, emerge collaboratively, the former with iterated verbal estimates, the latter often being signalled merely by facial expressions.

This study illustrates the need for team members to be ready and able to shift into alternative collaboration modes when delivery pressures are at their peak.

Lortie, J.,et al. (2023) How leadership moments are enacted within a strict hierarchy: The case of kitchen brigades in haute cuisine restaurants. Organization Studies . 44 (7), pp. 1081–1101. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221134225

Interdisciplinary Research

When academic teams from a range of disciplines get together to work on collaborative research, a number of new challenges exist around communication and the clash of different habitual norms of working.

This work studied interdisciplinary climate projects over several years, and concluded that foundational enabling factors to successful teamwork were:

- spending time together

- practising trust

- task talk

- negotiating meaning through discussions of language differences

- demonstrating presence (listening, getting excited)

- reflexive talk (reflecting on team dynamics and change)

- backstage communication (off-topic but self-revealing conversation)

- shared humour and laughter

Detrimental processes by contrast consisted of:

- negative humour and sarcasm

- debating expertise

- communicating boredom

- jockeying for power

Such work shows how the challenges of bringing together very different types of background and expertise are outweighed by the benefits gained from developing a shared understanding and a much richer view of a problem.

Thompson, J. (2009) Building Collective Communication Competence in Interdisciplinary Research Teams. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 37 (3), pp. 278–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880903025911