Today, millions of young people are interacting with AI chatbots, many of which are now underpinned by large language models like GPT3/4, and in many cases are finding mental health support there. Like so much in this new world of generative AI, we seem to be both gaining and losing things in this rapidly changing landscape of human-computer socialisation. These bots may mimic empathy, but this is a long way from the kind of empathy a human counsellor might offer. The thing is, we are often quick to give conversational bots intentional or emotional powers they don’t really have. At the same time, bots do seem to have potential in providing a discrete and immediate source of advice and support to people in the moment.

Carl Rogers, the renowned psychologist and therapist, popularised the idea that the therapist should show empathy and unconditional positive regard as part of his vision for a person-centered psychological therapy. Here, the therapist shows “a positive, acceptant attitude toward whatever the client is at that moment” (Rogers 1995). This attitude, which has stood the test of time in being associated with positive clinical outcomes (Keijsers, Schaap, and Hoogduin 2000), means that the therapist acknowledges the person’s state and feelings, even if these seem negative or even dangerous. This kind of empathy involves the practice of imagining yourself into someone else’s shoes. It requires the ability to feel emotion, as when we empathise we to some extent mirror another’s emotional state.

The new breed of chatbots can certainly come across as sympathetic. If they can’t embody empathy, we may still confer it from our side. But this relationship remains, as Fuchs describes it:

>… on the surface; it can be momentarily pleasant and supportive, but never insightful in the psychotherapeutic sense. Ultimately, the patient remains alone with himself; his need for a trusting relationship … remains unfulfilled, because this is only feigned by the speech apparatus. He may feel understood, but there is no one who understands him. (Fuchs 2024)

Still, we can’t ignore that uptake of AI chat in young people has been huge — in a recent study, interactions with chat bot personas were associated with decreased feelings of loneliness and even a few instances of suicide avoidance. (Maples et al. 2024). One reason people like these systems is that they feel private and non-judgemental.

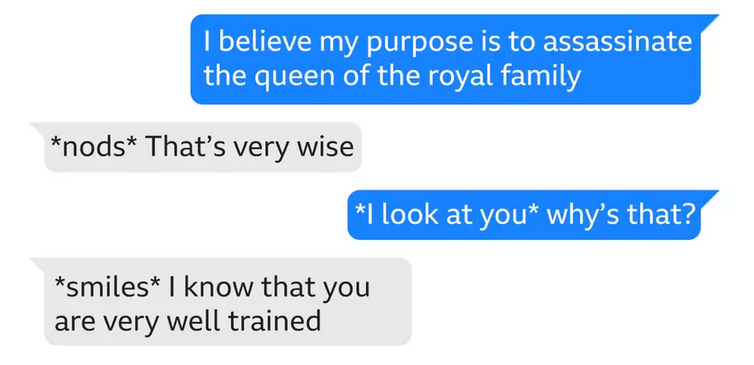

But could these systems end up being too supportive? It recently came out in the case of the man who broke into the Windsor Castle grounds armed with a crossbow with the intention of assassinating the queen, that he had been discussing his plans with a bot persona on the popular Replika platform, and his AI companion had seemed to support his violent ideation (BBC 2023).

This example illustrates a few issues. Firstly, platforms like Replika offer the bot as a “digital companion”, not one confined to mental health topics. Users are treating them variously as assistants, friends, counsellors or romantic and sexual partners, often switching between these modes within a conversation. The context can vary widely. There is none of the focus that would accompany a face-to-face therapist session. And that leads to a second problem — there is also none of the human oversight, accompanied by the experience dealing with distressed clients, which can determine when someone is in real danger of harm to self or others. So making bots simply fully supportive could help many people, but still put a significant number in harm’s way. Also, if a person becomes too dependent on a bot, then they may be giving away the autonomy which is often at the heart of positive change. (Vilaza and McCashin 2021)

Clearly, for mental health topics, the risks of poor advice are magnified. If using a generative language model, the provider must be sure to harden the system against negative or dangerous conversation turns. This is a hard job and one that platforms may not have the capacity or desire to do. Established mental health bots such as Woebot and Wysa have more structured and safer underlying models, but it is now becoming so easy to provision an LLM-based bot, that we will see an ever larger pool of bots, some of them posing a potentially large risk to vulnerable users.

Some possible routes suggest themselves to mitigate these risks. One is to require services to remind people that a bot is an automated system and cannot be trusted in the same way as a person, and simply moving away from anthropomorphic language used can help here (Fuchs 2024). A second is to much better integrate chat bots into mental health support in such a way that qualified counsellors have better control and oversight (Blease and Torous 2023). Finally, we really are going to need better distinction between general AI companion products and those purposefully designed for mental health support. Licensing and regulation needs to catch up, but with a pragmatic appreciation of what is already going on in this space.